Léopold Sédar Senghor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

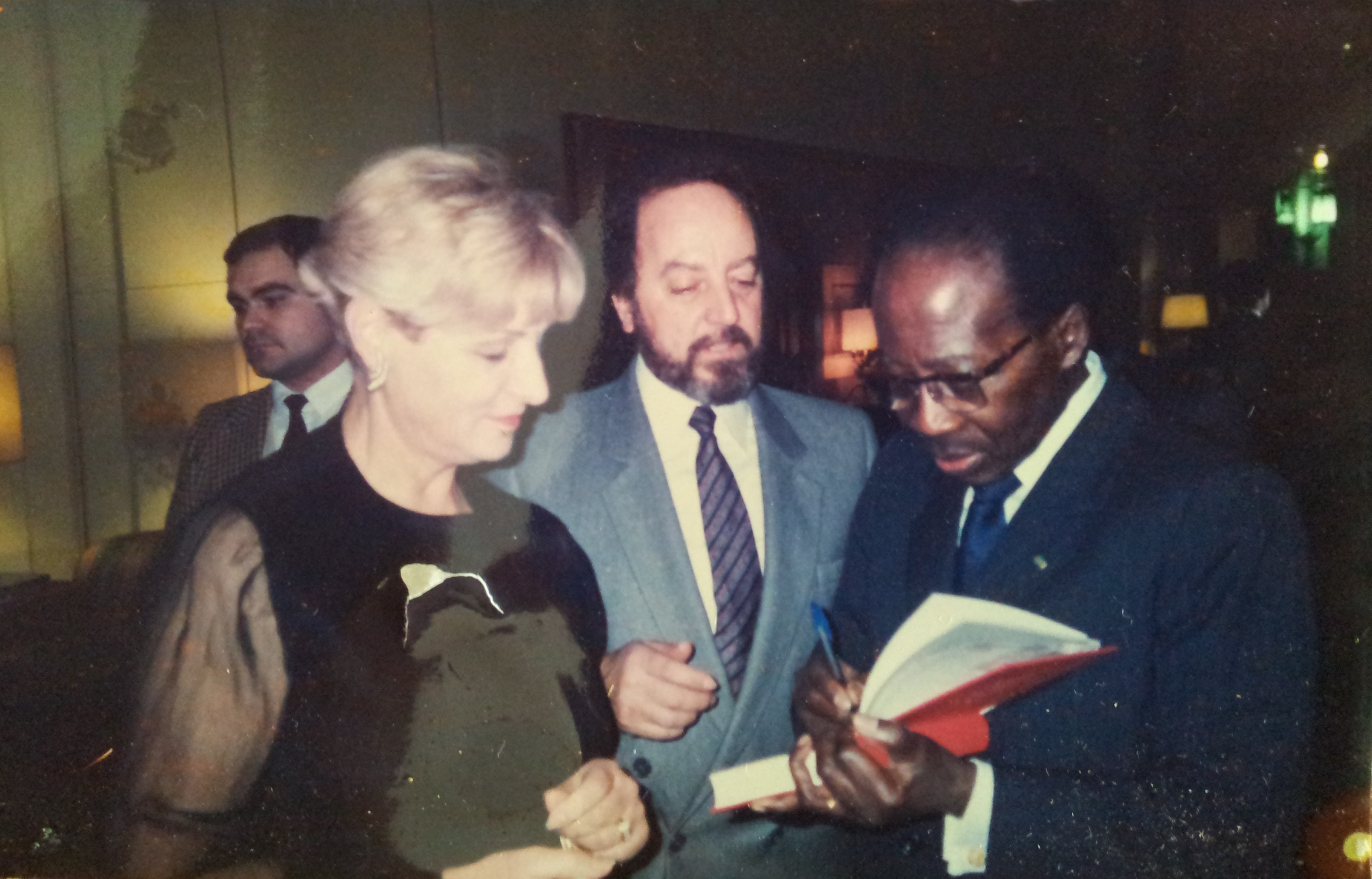

Léopold Sédar Senghor (; ; 9 October 1906 – 20 December 2001) was a

Senghor spent the last years of his life with his wife in Verson, near the city of

Senghor spent the last years of his life with his wife in Verson, near the city of

Senghor received several honours in the course of his life. He was made Grand-Croix of the

Senghor received several honours in the course of his life. He was made Grand-Croix of the

/ref> That same year, Senghor received anAéroport International Léopold Sédar Senghor

, official website.

The Passerelle Solférino in Paris was renamed after him in 2006, on the centenary of his birth.

His poetry was widely acclaimed, and in 1978 he was awarded the

His poetry was widely acclaimed, and in 1978 he was awarded the

With

With

Biography and guide to collected works

African Studies Centre, Leiden

Histoire des Signares de Gorée du 17ie au 19ie siécle

Poèmes de Léopold Sédar Senghor

Biographie par l'Assemblée nationale

Biographie par l'Academie française

''President Dia'' by William Mbaye (2012, english version) – Youtube

– Political documentary – 1957 to 1963 in Senegal (55')

Préface par Léopold Sédar Senghor à l'ouvrage collectif sur Le Nouvel Ordre Économique Mondiale

édité par

Semaine spéciale Senghor à l'occasion du centenaire de sa naissanceTexte sur le site de Sudlangues

Mamadou Cissé, "De l'assimilation à l'appropriation: essai de glottopolitique senghorienne»

Page on the French National Assembly website« Racisme? Non, mais Alliance Spirituelle »

{{DEFAULTSORT:Senghor, Leopold Sedar 1906 births 2001 deaths People from Thiès Region People of French West Africa Senegalese Roman Catholics Serer presidents Presidents of Senegal French Section of the Workers' International politicians Senegalese Democratic Bloc politicians Government ministers of France Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1945) Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1946) Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 2nd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fifth Republic Senegalese pan-Africanists Senegalese politicians Catholic socialists Senegalese Christian socialists National anthem writers Senegalese poets 20th-century male writers Prince des poètes Prix Guillaume Apollinaire winners Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni Members of the Académie Française French Army officers French Army personnel of World War II French prisoners of war in World War II French Resistance members Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Socialist rulers 20th-century Senegalese politicians

Senegalese

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

poet, politician and cultural theorist who was the first president of Senegal (1960–80).

Ideologically an African socialist, he was the major theoretician of Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

. Senghor was a proponent of African culture

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

, black identity and African empowerment within the framework of French-African ties. He advocated for the extension of full civil and political rights for France's African territories while arguing that French Africans would be better off within a federal French structure than as independent nation-states.

Senghor became the first President of independent Senegal. He fell out with his long-standing associate Mamadou Dia

Mamadou Dia (18 July 1910 – 25 January 2009) was a Senegalese politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Senegal from 1957 until 1962, when he was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned amidst allegations that he was p ...

who was Prime Minister of Senegal, arresting him on suspicion of fomenting a coup and imprisoning him for 12 years. Senghor established an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

single-party

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

state in Senegal where all rival political parties were prohibited.

Senghor was also the founder of the Senegalese Democratic Bloc

Senegalese Democratic Bloc (in French: ''Bloc Démocratique Sénégalais'') was a political party in Senegal, founded on 27 October 1948 by Léopold Sédar Senghor, following a split from the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). ...

party. Senghor was the first African elected as a member of the ''Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

''. He won the 1985 International Nonino Prize in Italy. He is regarded by many as one of the most important African intellectuals of the 20th century.

Early years: 1906–28

Léopold Sédar Senghor was born on 9 October 1906 in the city of Joal, some 110 kilometres south ofDakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

, capital of Senegal. His father, Basile Diogoye Senghor (pronounced: Basile Jogoy Senghor), was a wealthy peanut merchant belonging to the bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

Serer people

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group.

.Bibliographie, Dakar, Bureau de documentation de la Présidence de la République, 1982 (2e édition), 158 pp. Basile Senghor was said to be a man of great means and owned thousands of cattle and vast lands, some of which were given to him by his cousin the king of Sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side that is oppo ...

. Gnilane Ndiémé Bakhoum (1861–1948), Senghor's mother, the third wife of his father, a Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

with Fula

Fula may refer to:

*Fula people (or Fulani, Fulɓe)

*Fula language (or Pulaar, Fulfulde, Fulani)

**The Fula variety known as the Pulaar language

**The Fula variety known as the Pular language

**The Fula variety known as Maasina Fulfulde

*Al-Fula ...

origin who belonged to the Tabor tribe, was born near Djilor to a Christian family. She gave birth to six children, including two sons. Senghor's birth certificate states that he was born on 9 October 1906; however, there is a discrepancy with his certificate of baptism, which states it occurred on 9 August 1906. His Serer middle name ''Sédar'' comes from the Serer language

Serer, often broken into differing regional dialects such as Serer-Sine and Serer saloum, is a language of the kingdoms of Sine and Saloum branch of Niger–Congo spoken by 1.2 million people in Senegal and 30,000 in the Gambia as of 2009. It i ...

, meaning "one that shall not be humiliated" or "the one you cannot humiliate". His surname ''Senghor'' is a combination of the Serer words ''Sène'' (a Serer surname and the name of the Supreme Deity in Serer religion

The Serer religion, or ''a ƭat Roog'' ("the way of the Divine"), is the original religious beliefs, practices, and teachings of the Serer people of Senegal in West Africa. The Serer religion believes in a universal supreme deity called Roog ...

called '' Rog Sene'') and ''gor'' or ''ghor'', the etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

of which is ''kor'' in the Serer language

Serer, often broken into differing regional dialects such as Serer-Sine and Serer saloum, is a language of the kingdoms of Sine and Saloum branch of Niger–Congo spoken by 1.2 million people in Senegal and 30,000 in the Gambia as of 2009. It i ...

, meaning male or man. Tukura Badiar Senghor, the prince of Sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side that is oppo ...

and a figure from whom Léopold Sédar Senghor has been reported to trace descent, was a Serer noble.

At the age of eight, Senghor began his studies in Senegal in the Ngasobil

Ngazobil (also called Ngasobil) is a village in Senegal, located on the Petite Côte, south of Dakar.

History

Since the 19th century, Ngazobil has housed a Catholic mission, one of the oldest in Senegal, established by François Libermann of Save ...

boarding-school of the Fathers of the Holy Spirit. In 1922 he entered a seminary in Dakar. After being told the religious life was not for him, he attended a secular institution. By then, he was already passionate about French literature. He won distinctions in French, Latin, Greek and Algebra. With his Baccalaureate completed, he was awarded a scholarship to continue his studies in France.

"Sixteen years of wandering": 1928–1944

In 1928 Senghor sailed from Senegal for France, beginning, in his words, "sixteen years of wandering." Starting his post-secondary studies at theSorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, he quit and went on to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand (), also referred to simply as Louis-le-Grand or by its acronym LLG, is a public Lycée (French secondary school, also known as sixth form college) located on rue Saint-Jacques in central Paris. It was founded in the ...

to finish his prep course for entrance to the ''École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

'', a ''grande école

A ''grande école'' () is a specialised university that is separate from, but parallel and often connected to, the main framework of the French public university system. The grandes écoles offer teaching, research and professional training in s ...

''., Henri Queffélec, Robert Verdier

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

and Georges Pompidou

Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou ( , ; 5 July 19112 April 1974) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1969 until his death in 1974. He previously was Prime Minister of France of President Charles de Gaulle from 1962 to 196 ...

were also studying at this elite institution. After failing the entrance exam, Senghor prepared for his grammar ''Agrégation

In France, the ''agrégation'' () is a competitive examination for civil service in the French public education system. Candidates for the examination, or ''agrégatifs'', become ''agrégés'' once they are admitted to the position of ''professe ...

''. He was granted his ''agrégation'' in 1935 after a failed first attempt.

Academic career

Senghor graduated from theUniversity of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, where he received the Agrégation in French Grammar. Subsequently, he was designated professor at the universities of Tours and Paris, where he taught during the period 1935–45.

Senghor started his teaching years at the lycée René-Descartes in Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

; he also taught at the lycée Marcelin-Berthelot in Saint-Maur-des-Fosses near Paris. He also studied linguistics taught by Lilias Homburger at the ''École pratique des hautes études

The École pratique des hautes études (), abbreviated EPHE, is a Grand Établissement in Paris, France. It is highly selective, and counted among France's most prestigious research and higher education institutions. It is a constituent college o ...

''. He studied with prominent social scientists such as Marcel Cohen Marcel Samuel Raphaël Cohen (February 6, 1884 – November 5, 1974) was a French linguist. He was an important scholar of Semitic languages and especially of Ethiopian languages. He studied the French language and contributed much to general lingui ...

, Marcel Mauss

Marcel Mauss (; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and ...

and Paul Rivet

Paul Rivet (7 May 1876, Wasigny, Ardennes – 21 March 1958) was a French ethnologist known for founding the Musée de l'Homme in 1937. In his professional work, Rivet is known for his theory that South America was originally populated in pa ...

(director of the Institut d'ethnologie de Paris). Senghor, along with other intellectuals of the African diaspora who had come to study in the colonial capital, coined the term and conceived the notion of "négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

", which was a response to the racism still prevalent in France. It turned the racial slur ''nègre'' into a positively connoted celebration of African culture and character. The idea of ''négritude'' informed not only Senghor's cultural criticism and literary work, but also became a guiding principle for his political thought in his career as a statesman.

Military service

In 1939, Senghor was enrolled as a French army enlisted man (''2e Classe'') with the rank of private within the 59th Colonial Infantry division in spite of his higher education and of his 1932 acquisition of the French Citizenship. A year later in 1940, during theGerman invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* the 1746 War of the Austrian Succession, Austria-Italian forces supported by the British navy attemp ...

, he was taken prisoner by the Germans in la Charité-sur-Loire

La Charité-sur-Loire (before 1961: ''La Charité'') is a commune in the Nièvre department and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region of eastern France.

Geography

La Charité-sur-Loire lies on the right, eastern bank of the river Loire, about 25 km n ...

. He was interned in different camps, and finally at Front Stalag 230, in Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

. Front Stalag 230 was reserved for colonial troops captured during the war. German soldiers wanted to execute him and the others the same day they were captured, but they escaped this fate by yelling ''Vive la France, vive l'Afrique noire!'' ("Long live France, long live Black Africa!") A French officer told the soldiers that executing the African prisoners would dishonour the Aryan race

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people of Proto-Indo-European heritage as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern I ...

and the German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

. In total, Senghor spent two years in different prison camps, where he spent most of his time writing poems and learning enough German to read Goethe's poetry in the original. In 1942 he was released for medical reasons.Jamie Stokes. ''Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East'', Vol. 1. Infobase Publishing, 2009. , .

He resumed his teaching career while remaining involved in the resistance during the Nazi occupation.

Political career: 1945–1982

Colonial France

Senghor advocated for African integration within the French Empire, arguing that independence for small, weak territories would lead to the perpetuation of oppression, whereas African empowerment within a federal French Empire could transform it for the better. Once the war was over, Senghor was selected as Dean of the Linguistics Department with the ''École nationale de la France d'Outre-Mer

The Colonial School (french: École coloniale, also known colloquially as ) was a French public higher education institution or grande école, created in Paris in 1889 to provide training for public servants and administrators of the French colon ...

'', a position he would hold until Senegal's independence in 1960. While travelling on a research trip for his poetry, he met the local socialist leader, Lamine Guèye, who suggested that Senghor run for election as a member of the Assemblée nationale française. Senghor accepted and became ''député'' for the riding of Sénégal-Mauritanie, when colonies were granted the right to be represented by elected individuals. They took different positions when the train conductors on the Dakar-Niger line went on strike. Guèye voted against the strike, arguing the movement would paralyse the colony, while Senghor supported the workers, which gained him great support among Senegalese.

During the negotiations to write the French Constitution of 1946

The Constitution of the French Republic of 27 October 1946 was the constitution of the French Fourth Republic.

Adopted by the on 29 September 1946, and promulgated by Georges Bidault, president of the Provisional Government of the French ...

, Senghor pushed for the extension of French citizenship to all French territories. Four Senegalese communes had citizenship since 1916 – Senghor argued that this should be extended to the rest of France's territory. Senghor argued for a federal model whereby each African territory would govern its own internal affairs, and this federation would be part of a larger French confederation that ran foreign affairs, defense and development policies. Senghor opposed indigenous nationalism, arguing that African territories would develop more successfully within a federal model where each territory had its "negro-African personality" along with French experience and resources.

Political changes

In 1947, Senghor left the African Division of theFrench Section of the Workers International

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-day Socialist Party. The SFIO was foun ...

(SFIO), which had given enormous financial support to the social movement. With Mamadou Dia

Mamadou Dia (18 July 1910 – 25 January 2009) was a Senegalese politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Senegal from 1957 until 1962, when he was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned amidst allegations that he was p ...

, he founded the '' Bloc démocratique sénégalais'' (1948). They won the legislative elections of 1951, and Guèye lost his seat. Senghor was involved in the negotiations and drafting of the Fourth Republic's constitution.

Re-elected deputy in 1951 as an independent overseas member, Senghor was appointed state secretary to the council's president in Edgar Faure

Edgar Jean Faure (; 18 August 1908 – 30 March 1988) was a French politician, lawyer, essayist, historian and memoirist who served as Prime Minister of France in 1952 and again between 1955 and 1956.Thiès

Thiès (; ar, ثيس, Ṯyass; Noon: ''Chess'') is the third largest city in Senegal with a population officially estimated at 320,000 in 2005. It lies east of Dakar on the N2 road and at the junction of railway lines to Dakar, Bamako and St-L ...

, Senegal in November 1956 and then advisory minister in the Michel Debré

Michel Jean-Pierre Debré (; 15 January 1912 – 2 August 1996) was the first Prime Minister of the French Fifth Republic. He is considered the "father" of the current Constitution of France. He served under President Charles de Gaulle from 195 ...

's government from 23 July 1959 to 19 May 1961. He was also a member of the commission responsible for drafting the Fifth Republic's constitution, general councillor for Senegal, member of the ''Grand Conseil de l'Afrique Occidentale Francaise'' and member for the parliamentary assembly of the European Council

The European Council (informally EUCO) is a collegiate body that defines the overall political direction and priorities of the European Union. It is composed of the heads of state or government of the EU member states, the President of the E ...

.

In 1964 Senghor published the first volume of a series of five, titled ''Liberté''. The book contains a variety of speeches, essays and prefaces.

Senegal

Senghor supported federalism for newly independent African states, a type of "French Commonwealth", while retaining a degree of French involvement: Since federalism was not favoured by the African countries, he decided to form, along withModibo Keita Modibo or more correctlyMoodibbo in Fula or Fulfulde Orthography is a given name in some Fulɓe or Fulani regions, while in some regions it's used as a form of respect which means a learned scholar. Others are named moodibbo after one's parents or g ...

, the Mali Federation

The Mali Federation ( ar, اتحاد مالي) was a federation in West Africa linking the French colonies of Senegal and the Sudanese Republic (or French Sudan) for two months in 1960. It was founded on 4 April 1959 as a territory with self-ru ...

with former French Sudan

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

(present-day Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

). Senghor was president of the Federal Assembly until its failure in 1960.

Afterwards, Senghor became the first President of the Republic of Senegal, elected on 5 September 1960. He is the author of the Senegalese national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European n ...

. The prime minister, Mamadou Dia

Mamadou Dia (18 July 1910 – 25 January 2009) was a Senegalese politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Senegal from 1957 until 1962, when he was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned amidst allegations that he was p ...

, was in charge of executing Senegal's long-term development plan, while Senghor was in charge of foreign relations. The two men quickly disagreed. In December 1962, Mamadou Dia was arrested under suspicion of fomenting a ''coup d'état''. He was held in prison for 12 years. Following this, Senghor established an authoritarian presidential regime where all rival political parties were suppressed.

On 22 March 1967, Senghor survived an assassination attempt. The suspect, Moustapha Lô Moustapha Lô (died 15 June 1967) was a Senegalese man who attempted to assassinate Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor on 22 March 1967 at the Dakar Grand Mosque. Lô was convicted of treason, was sentenced to death by a Senegalese cour ...

, pointed his pistol towards the President after he had participated in the sermon of Tabaski

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's ...

, but the gun did not fire. Lô was sentenced to death for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and executed on 15 June 1967, even though it remained unclear if he had actually wanted to kill Senghor.

Following an announcement at the beginning of December 1980, Senghor resigned his position at the end of the year, before the end of his fifth term. Abdou Diouf replaced him as the head of the country. Under his presidency, Senegal adopted a multi-party system (limited to three: socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

). He created a performing education system. Despite the end of official colonialism, the value of Senegalese currency continued to be fixed by France, the language of learning remained French, and Senghor ruled the country with French political advisors.

Francophonie

He supported the creation ofla Francophonie

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

and was elected vice-president of the High Council of the Francophonie. In 1982, he was one of the founders of the Association France and developing countries whose objectives were to bring attention to the problems of developing countries, in the wake of the changes affecting the latter.

Académie française: 1983–2001

He was elected a member of theAcadémie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

on 2 June 1983, at the 16th seat where he succeeded Antoine de Lévis Mirepoix. He was the first African to sit at the Académie. The entrance ceremony in his honour took place on 29 March 1984, in presence of French President François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

. This was considered a further step towards greater openness in the Académie, after the previous election of a woman, Marguerite Yourcenar

Marguerite Yourcenar (, , ; born Marguerite Antoinette Jeanne Marie Ghislaine Cleenewerck de Crayencour; 8 June 1903 – 17 December 1987) was a Belgian-born French novelist and essayist, who became a US citizen in 1947. Winner of the ''Prix Fem ...

.

In 1993, the last and fifth book of the ''Liberté'' series was published: ''Liberté 5: le dialogue des cultures.''

Personal life and death

Senghor's first marriage was to Ginette Éboué (1 March 1923 – 1992), daughter of Félix Éboué. They married on 9 September 1946 and divorced in 1955. They had two sons, Francis in 1947 and Guy in 1948. His second wife, Colette Hubert r(20 November 1925 – 18 November 2019), who was from France, became Senegal's firstFirst Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

upon independence in 1960. Senghor had three sons between his two marriages.

Senghor spent the last years of his life with his wife in Verson, near the city of

Senghor spent the last years of his life with his wife in Verson, near the city of Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

. Officials attending the ceremony included Raymond Forni

Raymond Forni (20 May 1941 – 5 January 2008) was a French Socialist politician.

Biography

The son of an Italian immigrant from Piedmont, Forni was born in Belfort, in 1941. His father died when he was 11. At 17, he had to stop studying, a ...

, president of the Assemblée nationale

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are know ...

and Charles Josselin, state secretary for the minister of foreign affairs, in charge of the Francophonie. Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as Ma ...

(who said, upon hearing of Senghor's death: "Poetry has lost one of its masters, Senegal a statesman, Africa a visionary and France a friend") and Lionel Jospin

Lionel Robert Jospin (; born 12 July 1937) is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 1997 to 2002.

Jospin was First Secretary of the Socialist Party from 1995 to 1997 and the party's candidate for President of France in ...

, respectively president of the French Republic

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

and the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, did not attend. Their failure to attend Senghor's funeral made waves as it was deemed a lack of acknowledgement for what the politician had been in his life. The analogy was made with the Senegalese Tirailleurs

The Senegalese Tirailleurs (french: Tirailleurs Sénégalais) were a corps of colonial infantry in the French Army. They were initially recruited from Senegal,

French West Africa and subsequently throughout Western, Central and Eastern Africa: t ...

who, after having contributed to the liberation of France, had to wait more than forty years to receive an equal pension (in terms of buying power) to their French counterparts. The scholar Érik Orsenna

Érik Orsenna is the pen-name of Érik Arnoult (born 22 March 1947) a French politician and novelist. After studying philosophy and political science at the Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris ("Sciences Po"), Orsenna specialized in economic ...

wrote in the newspaper ''Le Monde

''Le Monde'' (; ) is a French daily afternoon newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average circulation of 323,039 copies per issue in 2009, about 40,000 of which were sold abroad. It has had its own website si ...

'' an editorial entitled "J'ai honte" (I am ashamed).

Legacy

Although a socialist, Senghor avoided theMarxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and anti-Western ideology that had become popular in post-colonial Africa, favouring the maintenance of close ties with France and the western world.

Senghor's tenure as president was characterised by the development of African socialism

African socialism or Afrosocialism is a belief in sharing economic resources in a traditional African way, as distinct from classical socialism. Many African politicians of the 1950s and 1960s professed their support for African socialism, althou ...

, which was created as an indigenous alternative to Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, drawing heavily from the ''négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

'' philosophy. In developing this, he was assisted by Ousmane Tanor Dieng

Ousmane Tanor Dieng (January 2, 1947 – July 15, 2019) was the First Secretary of the Socialist Party of Senegal. He was vice-president of the Socialist International from 1996 until his death.

Personal life

Born in 1947 in Nguéniène, Seneg ...

. On 31 December 1980, he retired in favour of his prime minister, Abdou Diouf. Politically, Senghor's stamp can also be identified today. With regards to Senegal in particular, his willful abdication of power to his successor, Abdou Diouf, led to Diouf's peaceful leave from office as well. Senegal's special relationship to France and economic legacy are more highly contested, but Senghor's impact on democracy remains nonetheless. Senghor managed to retain his identity as both a poet and a politician even throughout his busy careers as both, living by his philosophy of achieving equilibrium between competing forces. Whether it was France and Africa, poetics and politics, or other disparate parts of his identity, Senghor balanced the two.

Literarily, Senghor's influence on political thought and poetic form are wide reaching even through to our modern day. Senghor's poetry endures as the "record of an individual sensibility at a particular moment in history," capturing the spirit of the Négritude movement at its peak, but also marks a definitive place in literary history. Senghor's thoughts were exceedingly radical for this time, arguing that Africans could only progress if they developed a culture distinct and separate from the colonial powers that oppressed them, pushing against popular thought at the time. Senghor was deeply influenced by poets from the US like Langston Hughes, and his work in turn resonates among today's young US population despite the generations that have passed.

Seat number 16 of the Académie was vacant after the Senegalese poet's death. He was ultimately replaced by another former president, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

.

Honours and awards

Senghor received several honours in the course of his life. He was made Grand-Croix of the

Senghor received several honours in the course of his life. He was made Grand-Croix of the Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, Grand-Croix of the l'Ordre national du Mérite

The Ordre national du Mérite (; en, National Order of Merit) is a French order of merit with membership awarded by the President of the French Republic, founded on 3 December 1963 by President Charles de Gaulle. The reason for the order's esta ...

, commander of arts and letters. He also received academic palms and the Grand Cross of the National Order of the Lion

("One People, One Goal, One Faith")

, eligibility =

, criteria =

, status = Active

, founder =

, head_title = Grand Master

, head = Macky Sall

, head2_title = Grand Chancellor

, head2 ...

. His war exploits earned him the Reconnaissance Franco-alliée Medal of 1939–1945 and the Combattant Cross of 1939–1945. He received honorary doctorates from thirty-seven universities.

Senghor received the Commemorative Medal of the 2500th Anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire on 14 October 1971.

On 13 November 1978, he was created a Knight of the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Order of Isabella the Catholic ( es, Orden de Isabel la Católica) is a Spanish civil order and honor granted to persons and institutions in recognition of extraordinary services to the homeland or the promotion of international relations a ...

of Spain. Members of the order at the rank of Knight and above enjoy personal nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

and have the privilege of adding a golden heraldic mantle to their coats of arms. Those at the rank of the Collar also receive the official style "His or Her Most Excellent Lord".Boletín Oficial del Estado./ref> That same year, Senghor received an

honoris causa

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

from the University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca ( es, Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX. It is th ...

.

In 1983 he was awarded the Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize

Doctor is an academic title that originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb 'to teach'. It has been used as an academic title in Europe since the 13th century, w ...

by the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Wü ...

.

The Senghor French Language International University, named after him was officially opened in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

in 1990.

In 1994 he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the African Studies Association

The African Studies Association (ASA) is a US-based association of scholars, students, practitioners, and institutions with an interest in the continent of Africa. Founded in 1957, the ASA is the leading organization of African Studies in North ...

; however, there was controversy about whether he met the standard of contributing "a lifetime record of outstanding scholarship in African studies and service to the Africanist community." Michael Mbabuike, president of the New York African Studies Association (NYASA), said that the award also honours those who have worked "to make the world a better place for mankind."

The airport of Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

was renamed '' Aéroport International Léopold Sédar Senghor'' in 1996, on his 90th birthday., official website.

Acknowledgement

* Member of theAcadémie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

* Member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

* Member of the Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste

Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste in München (Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts) is an association of renowned personalities in Munich, Bavaria. It was founded by the Free State of Bavaria in 1948, continuing a tradition established in 1808 by ...

* Member of the Royal Academy of Morocco

* Honorary Fellow

Honorary titles (professor, reader, lecturer) in academia may be conferred on persons in recognition of contributions by a non-employee or by an employee beyond regular duties. This practice primarily exists in the UK and Germany, as well as in m ...

of the Sahitya Akademi

The Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, is an organisation dedicated to the promotion of literature in the languages of India. Founded on 12 March 1954, it is supported by, though independent of, the Indian government. Its of ...

Quote: Poet, President of Senegal,

and theorist of “Négritude” Leopold Sangor was elected the first Honorary Fellow of the Sahitya Akademi in 1974. This group was to complement the category of “Fellows of the Akademi” whose number was at no time to exceed twenty-one in total and who were to be living Indian writers of undisputed excellence — “the immortals of literature.”

Honorary degrees

*Paris-Sorbonne University

Paris-Sorbonne University (also known as Paris IV; french: Université Paris-Sorbonne, Paris IV) was a public research university in Paris, France, active from 1971 to 2017. It was the main inheritor of the Faculty of Humanities of the Universit ...

* Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

* Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

* University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

* Université catholique de Louvain

The Université catholique de Louvain (also known as the Catholic University of Louvain, the English translation of its French name, and the University of Louvain, its official English name) is Belgium's largest French-speaking university. It ...

* Université de Montréal

The Université de Montréal (UdeM; ; translates to University of Montreal) is a French-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university's main campus is located in the Côte-des-Neiges neighborhood of Côte-de ...

* Université Laval

Université Laval is a public research university in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. The university was founded by royal charter issued by Queen Victoria in 1852, with roots in the founding of the Séminaire de Québec in 1663 by François de Montmo ...

* Goethe University Frankfurt

Goethe University (german: link=no, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main) is a university located in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It was founded in 1914 as a citizens' university, which means it was founded and funded by the wealt ...

* University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich histor ...

* University of Salzburg

The University of Salzburg (german: Universität Salzburg), also known as the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg (''Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg'', PLUS), is an Austrian public university

A public university or public college is a univ ...

* Paris Descartes University

* University of Bordeaux

The University of Bordeaux (French: ''Université de Bordeaux'') is a public university based in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France.

It has several campuses in the cities and towns of Bordeaux, Dax, Gradignan, Périgueux, Pessac, and Ta ...

* University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (french: Université de Strasbourg, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, Alsace, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers.

The French university traces its history to the ea ...

* Nancy 2 University

Nancy 2 University (''Université Nancy 2'') was a French university located in Nancy, France. It was a member of the Nancy-Université federation, a group of the three higher education institutions in Nancy.

* University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from B ...

* University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca ( es, Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX. It is th ...

* University of Évora

The University of Évora (''Universidade de Évora'') is a public university in Évora, Portugal. It is the second oldest university in the country, established in 1559 by the cardinal Henry, and receiving University status in April of the same ...

* Federal University of Bahia

The Federal University of Bahia ( pt, Universidade Federal da Bahia, UFBA) is a public university located mainly in the city of Salvador. It is the largest university in the state of Bahia and one of Brazil's most prestigious educational institu ...

Summary of Orders received

Senegalese national honours

Foreign honours

Poetry

His poetry was widely acclaimed, and in 1978 he was awarded the

His poetry was widely acclaimed, and in 1978 he was awarded the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca

The Prix mondial Cino Del Duca (Cino Del Duca World Prize) is an international literary award. With an award amount of , it is among the richest literary prizes.

Origins and operations

It was established in 1969 in France by Simone Del Duca (191 ...

.

His poem "A l'appel de la race de Saba", published in 1936, was inspired by the entry of Italian troops in Addis Ababa.

In 1948, Senghor compiled and edited a volume of Francophone poetry called ''Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache'' for which Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

wrote an introduction, entitled "Orphée Noir" (Black Orpheus).

For his epitaph was a poem he had written, namely:

:''Quand je serai mort, mes amis, couchez-moi sous Joal-l'Ombreuse.''

:''Sur la colline au bord du Mamanguedy, près l'oreille du sanctuaire des Serpents.''

:''Mais entre le Lion couchez-moi et l'aïeule Tening-Ndyae.''

:''Quand je serai mort mes amis, couchez-moi sous Joal-la-Portugaise.''

:''Des pierres du Fort vous ferez ma tombe, et les canons garderont le silence.''

:''Deux lauriers roses-blanc et rose-embaumeront la Signare.''

:''When I'm dead, my friends, place me below Shadowy Joal,''

:''On the hill, by the bank of the Mamanguedy, near the ear of Serpents' Sanctuary.''

:''But place me between the Lion and ancestral Tening-Ndyae.''

:''When I'm dead, my friends, place me beneath Portuguese Joal.''

:''Of stones from the Fort build my tomb, and cannons will keep quiet.''

:''Two oleanders – white and pink – will perfume the Signare.''

Négritude

With

With Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (; ; 26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author, and politician. He was "one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature" and coined the word in French. He founded the Par ...

and Léon Damas

Léon-Gontran Damas (March 28, 1912 – January 22, 1978) was a French poet and politician. He was one of the founders of the Négritude movement. He also used the pseudonym Lionel Georges André Cabassou.

Biography

Léon Damas was born in Ca ...

, Senghor created the concept of ''Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

'', an important intellectual movement that sought to assert and to valorise what they believed to be distinctive African characteristics, values, and aesthetics. One of these African characteristics that Senghor theorised was asserted when he wrote "the Negro has reactions that are more ''lived,'' in the sense that they are more direct and concrete expressions of the sensation and of the stimulus, and so of the object itself with all its original qualities and power." This was a reaction against the too strong dominance of French culture in the colonies, and against the perception that Africa did not have culture developed enough to stand alongside that of Europe. In that respect ''négritude'' owes significantly to the pioneering work of Leo Frobenius

Leo Viktor Frobenius (29 June 1873 – 9 August 1938) was a German self-taught ethnologist and archaeologist and a major figure in German ethnography.

Life

He was born in Berlin as the son of a Prussian officer and died in Biganzolo, Lago ...

.

Building upon historical research identifying ancient Egypt with black Africa, Senghor argued that sub-Saharan Africa and Europe are in fact part of the same cultural continuum, reaching from Egypt to classical Greece, through Rome to the European colonial powers of the modern age. Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "Nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, developed mainly by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians of the African ...

was by no means—as it has in many quarters been perceived—an anti-white racism, but rather emphasised the importance of dialogue and exchange among different cultures (e.g., European, African, Arab, etc.).

A related concept later developed in Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

's Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

is that of '' authenticité'' or Authenticity.

Décalage

In colloquial French, the term décalage is used to describe jetlag, lag or a general discrepancy between two things. However, Senghor uses the term to describe the unevenness in the African Diaspora. The complete phrase he uses is "Il s'agit, en réalité, d'un simple décalage—dans le temps et dans l'espace", meaning that between Black Africans and African Americans there exists an inconsistency, both temporally and spatially. The time element points to the advancing or delaying of a schedule or agenda, while the space aspects designates the displacing and shifting of an object. The term points to "a bias that refuses to pass over when one crosses the water". He asks, how can we expect any sort of solidarity or intimacy from two populations that diverged over 500 years ago?Works of Senghor

*''Prière aux masques'' (c. 1935 – published in collected works during the 1940s). *''Chants d'ombre'' (1945) *''Hosties noires'' (1948) *''Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache'' (1948) *''La Belle Histoire de Leuk-le-Lièvre'' (1953) *''Éthiopiques'' (1956) *''Nocturnes'' (1961). (English tr. by Clive Wake and John O. Reed, ''Nocturnes'', London: Heinemann Educational, 1969.African Writers Series

The African Writers Series (AWS) is a collection of books written by African novelists, poets and politicians. Published by Heinemann (publisher), Heinemann, 359 books appeared in the series between 1962 and 2003.

The series has provided an int ...

71)

*''Nation et voie africaine du socialisme'' (1961)

*''Pierre Teilhard de Chardin et la politique africaine'' (1962)

*''Poèmes'' (1964).

*''Lettres de d'hivernage'' (1973)

*''Élégies majeures'' (1979)

*''La Poésie de l'action: conversation avec Mohamed Aziza'' (1980)

*''Ce que je crois'' (1988)

See also

*Serer people

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group.

*List of Senegalese writers

__NOTOC__

This is a list of prominent Senegalese authors (by surname)

A - G

* Agbo, Berte-Evelyne, poet, also connected with Benin

* Bâ, Mariama (1929–1981), French-language novelistSee the entry in Douglas Killam & Ruth Rowe, eds., ''The Co ...

References

Further reading

*Armand Guibert & Seghers Nimrod (2006), ''Léopold Sédar Senghor'', Paris (1961 edition by Armand Guibert). *Sources from this article were taken from the equivalent French article :fr:Léopold Sédar Senghor. *External links

Biography and guide to collected works

African Studies Centre, Leiden

Histoire des Signares de Gorée du 17ie au 19ie siécle

Poèmes de Léopold Sédar Senghor

Biographie par l'Assemblée nationale

Biographie par l'Academie française

''President Dia'' by William Mbaye (2012, english version) – Youtube

– Political documentary – 1957 to 1963 in Senegal (55')

Préface par Léopold Sédar Senghor à l'ouvrage collectif sur Le Nouvel Ordre Économique Mondiale

édité par

Hans Köchler

Hans Köchler (born 18 October 1948) is a retired professor of philosophy at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, and president of the International Progress Organization, a non-governmental organization in consultative status with the United Na ...

(1980) (facsimilé)Semaine spéciale Senghor à l'occasion du centenaire de sa naissance

Mamadou Cissé, "De l'assimilation à l'appropriation: essai de glottopolitique senghorienne»

Page on the French National Assembly website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Senghor, Leopold Sedar 1906 births 2001 deaths People from Thiès Region People of French West Africa Senegalese Roman Catholics Serer presidents Presidents of Senegal French Section of the Workers' International politicians Senegalese Democratic Bloc politicians Government ministers of France Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1945) Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1946) Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 2nd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fifth Republic Senegalese pan-Africanists Senegalese politicians Catholic socialists Senegalese Christian socialists National anthem writers Senegalese poets 20th-century male writers Prince des poètes Prix Guillaume Apollinaire winners Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni Members of the Académie Française French Army officers French Army personnel of World War II French prisoners of war in World War II French Resistance members Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Socialist rulers 20th-century Senegalese politicians